Key Points

- Early warnings are considered the ‘jewel in the crown’ of NEC Contracts.

- NEC contractors and project (or service) managers must notify each other of anything that could increase prices, delay progress or impair performance as soon as they become aware of it.

- This article makes seven practical suggestions to make the early warning process more effective.

The early warning process has been described as the ‘jewel in the crown’ of NEC Contracts. But over-complicating the process, being fearful of the consequences of not notifying, and playing contractual games can undermine its effectiveness.

The following seven practical tips should help to ensure that both parties receive the full benefit of early warnings.

1. Delegate project manager’s power

Under clause 15.1 of the NEC4 Engineering and Constrution Contract (ECC), Term Service Contract (TSC) and Professional Service Contract (PSC), only the contractor and project or service manager can notify an early warning.

However, project and service managers are often remote from the day-to-day goings on in a design office or on site but can delegate their powers. This means there are likely to be delays in notification and hence resolution – by which I mean agreed actions – to the detriment of progress.

So, project or service managers need to delegate the power to notify early warnings down to people where work the work is being done. It follows they should also delegate the power to agree minor actions at resulting ad-hoc early warning meetings, including instructing minor changes to the scope.

2. Agree practical guidelines for notifying

If clause 15.1 is taken literally, both the contractor and project or service manager should notify early warnings for every possible event, however unlikely and small in potential impact. Further, if the contractor does not do this and the early warning turns into a compensation event, then the assessment could be reduced. As such there is a financial incentive for the contractor to notify everything.

Here are some suggested common-sense guidelines.

- If the contractor or project or service manager thinks it can deal with the matter and it is likely there will be no effect on the prices, completion or performance, just do the actions.

- If a party thinks a matter is more than likely to have an impact – even though initially it thought it could deal with the matter – it notifies.

- If a party thinks the other can help it deal with the matter, it notifies.

Also exercise common sense when it comes to low probability, high impact risks. For example, it might be a 5% probability risk, but if it is a £1 million risk on a £10 million contract, the other party will want to know.

Finally, project and service managers should be forgiving to a contractor if a matter moves from the first bullet to the second and becomes a compensation event. If the contractor is doing what is agreed, project managers should not reduce their assessment as the contractor will revert to notifying everything.

3. Phrase notifications constructively

Early warning notifications should not include aggressive or blaming language. Such ‘wince-inducing’ words put the other party’s back up, which is not conducive to good project management. In a similar vein, people are much more receptive to a problem if it comes with a solution, even if that is not the one ultimately adopted. Many contractors do this as a matter of policy because of the positive tone it sets. The pro-formas used for notifications, including those on cloud-based systems, should reflect this.

4. Encourage early warning meetings at site level

When a matter emerges, it needs to be resolved efficiently and quickly with minimal disruption to progress. That means small, prompt, ad-hoc meetings with the relevant people who are empowered to make decisions.

If resolution is held over to a regular early warning meeting, not only will the work be disrupted but it will also probably take longer as all the people at the meeting will want to have their say. A five-minute discussion may turn into a half hour one; multiply this by ten early warnings and a whole day can disappear.

Indeed, the more actions that are made outside of regular meetings, the more the regular meeting can monitor whether actions have been done and been effective, and to close out early warning matters which are no longer relevant. It therefore becomes shorter.

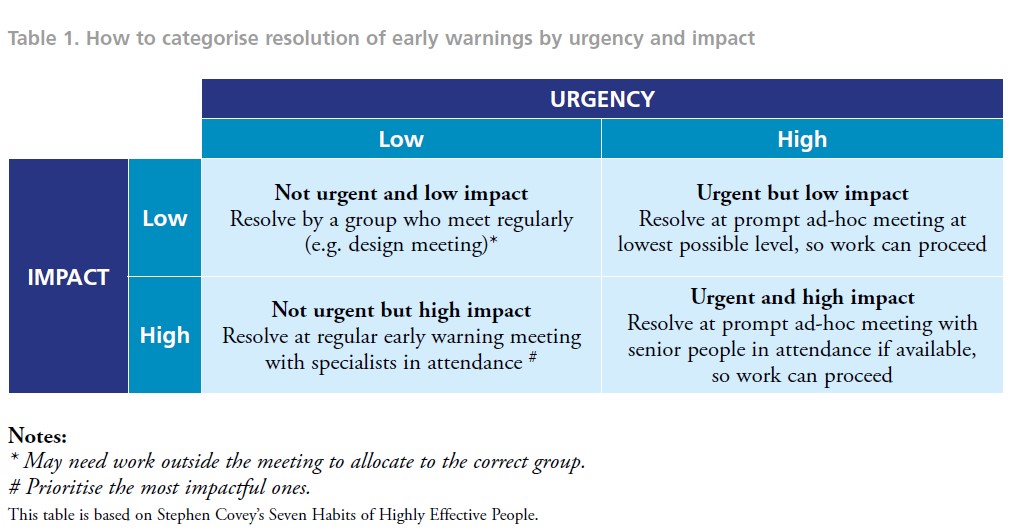

5. Categorise resolution on urgency and impact

Under NEC3, the word ‘risk’ was frequently used within the early warning clauses which caused confusion. For example, project managers wrongly rejected early warnings on the basis they were happening. It is also led to early warnings being prioritised on probability and impact, whether using Excel spreadsheets or cloud-based systems.

It is more useful to categorise early warnings by urgency and impact (see Table 1, which is based on Stephen Covey’s Seven Habits of Highly Effective People). Having done this, allocate responsibility for their resolution accordingly

6. Contractor leads the early warning process

In an Option A (priced contract with activity schedule), the contractor manages its supply chain of designers and specialist subcontractors. Most early warnings will therefore come from the supply chain and be resolved between them and the contractor. Obviously, the project or service manager should know about the major ones, but it does not make sense for the project or service manager to administrate all of them when they are not involved with most of them.

In such situations it makes more sense for the contractor to lead, and hence administrate, the early warning procedure. However, this should not be seen as absolving the project or service manager from taking actions where they can help resolve a matter. It also cannot be done without the contractor’s permission as the administration of early warning process by the project or service manager is expressed at condition of contract level, not in the scope.

7. Use risk management techniques

Many early warnings are not notified soon enough as people are not looking far enough ahead. Vaguely expressed risks in risk registers, such as unexpected ground conditions, should be regularly reviewed and turned into early warnings with specific responses. If a risk turns out to be unfounded (such as a survey shows ground conditions are as expected), this can be used to modify the probability of risk in the risk register, potentially freeing up funds for use elsewhere.

This can increasingly be done with big data and artificial intelligence processing power, which are now able to give far better predictions than traditional risk management techniques of where risk and uncertainty lie and their effects