Key Points

- Clients can use the option X29 performance table in NEC4 ECC contracts to include positive and negative incentives for the contractor to reduce whole-life cost.

- For significant elements of operational expenditure, contractors can be required to state the performance the asset will achieve.

- Parties can pre-agree the ‘cost’ of particular failures and so properly incentivise the contractor to minimise the operational expenditure of the finished asset.

In July 2022 NEC published the new NEC4 secondary option X29 on climate change (O’Connor, 2022), which enables clients to set specific climate-change targets in a new ‘Performance Table’. However, the new table can be used to set targets for anything, so another way of using X29 is to facilitate procurement based on whole-life cost rather than just capital cost. This will also help to reduce climate impacts. This article develops an earlier article on using option X17 on performance damages to incentivise lower whole-life cost (Patterson and Trebes, 2015a.) NEC users can of course use X21 for whole-life cost. However, X29 is arguably better as it enables clients to include both positive and negative incentives.

Understanding whole-life cost

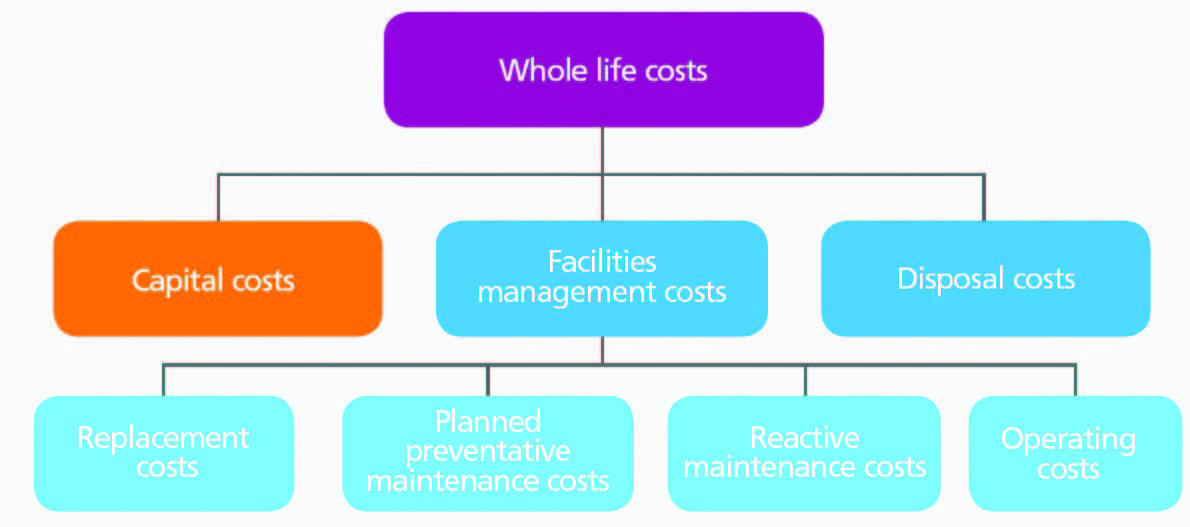

Most clients think long term. They realise their projects will need capital expenditure and result in a need for operational expenditure over the lifetime of the asset. The whole-life cost of the asset can be calculated as the net present cost based on the cash forecast to be expended, discounted over the likely lifetime of the asset. Figure 1 shows one way of categorising the elements of the whole-life cost of an asset.

The procurement route that directly encourages bidders to select the option with the lowest whole-life cost is the one that makes the contractor responsible for designing, building and operating the asset (Patterson and Trebes, 2013). This is now possible with the NEC4 Design, Build and Operate Contract (DBO). If the client does not have the cash for the capital expenditure, it can choose to let a contract for design, build, finance and operation using project finance, which is often the route used in public−private partnership arrangements (Patterson and Trebes, 2015b).

However, the client may have good reasons to want to operate the asset itself. In that case, if the client is requiring the contractor to design and build the asset, it may be appropriate to incentivise the contractor to deliver the solution to its requirements with the lowest net present cost. In the UK this is encouraged by the Public Contracts Regulations and internationally by funding institutions. This article explains how a client can procure for lowest net present cost using the NEC4 Engineering and Construction Contract (ECC) using secondary option X29.

Early contractor involvement

One way of selecting the best solution based on net present cost is through extensive design development and ‘optioneering’. This might be prior to defining the client’s detailed requirements in a construction contract, or it could be during the first stage of an ‘early contractor involvement’ (ECI) procurement route, working with the contractor in a stage one to arrive at a solution for stage two for detailed design and construction. In NEC4 ECC one can set up ECI using option X22. The agreement of the X29 performance table (see below) could be part of the work in ECI stage one.

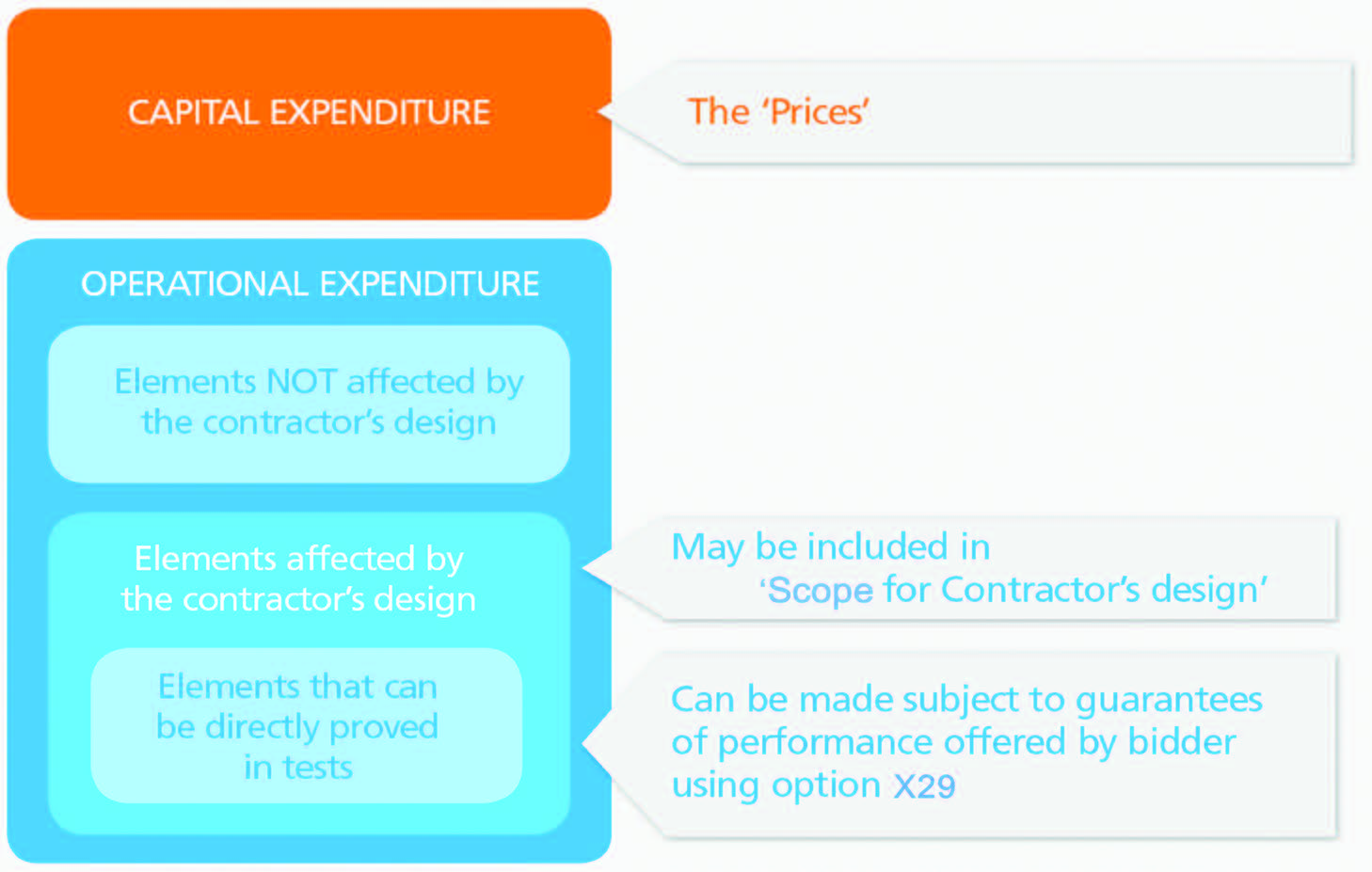

Construction contracts are mainly set up to cover the process of designing and delivering an asset. As such they tend to focus on the capital expenditure required to deliver the asset. If the procurement is to incentivise lowest net present cost, it will have to build in the operational expenditure of the asset.

Figure 2 shows that operational expenditure can be considered to be built up of different components: elements of operational expenditure that can be directly proven in defined tests; other elements of operational expenditure significantly affected by the contractor’s design; and elements of operational expenditure not significantly affected by the contractor’s design.

As an example, consider a simple water transfer scheme in which the client’s requirement is to transfer a stated flow rate of water from a river intake up to a storage reservoir. Power costs for pumping will contribute significantly to the operational expenditure and will be dependent on the diameter and number of pipelines used and the efficiency of the pumps installed. In principle, smaller pipes will have a smaller capital expenditure, but require more pumping capacity (more capital expenditure) and higher pumping costs (operational expenditure). Logically the contractor should be given as much flexibility as possible to choose its design solution to miminise the net present cost to the client.

Using the performance table

For significant elements of operational expenditure that can be directly tested and proven, a bidder can be required to state the performance the asset will achieve. ECC option X29 could be used to allow the bidder to offer a guaranteed level of performance, for example, the power consumption, in the performance table.

X29.12(3) states: ‘At the dates stated in the Performance Table…if the relevant performance does not meet the target stated in the Performance Table, the Contractor pays the amount stated in the Performance Table… if the relevant performance exceeds or meets the target stated in the Performance Table, the Contractor is paid the amount stated in the Performance Table’, (bullets omitted). This effectively allows and requires the contractor to pay a pre-priced ‘get out of jail’ card rather than have to correct what would have been a defect if the obligation was in the scope. Note that X29.12(4) states, ‘Information in the Performance Table is not Scope.’

If X29 was not included and the performance requirement instead was stated in the scope (or, more likely, the scope provided by the contractor for its design) and the performance did not meet the requirement, then the contractor could offer a commercial deal to the client to accept the defect, as it can for any defect under clause 45. The benefit of using X29 is that the parties can pre-agree the ‘cost’ of particular defects and so properly incentivise the contractor to minimise the operational expenditure of the finished asset. More importantly for the financial element of bid evaluation, the client can select the solution with the lowest whole-life cost including for the guaranteed performance levels.

On the positive side the client can, in the performance table, also give the contractor a positive incentive to beat the target that was set. Such an incentive should genuinely encourage the contractor to design for reduced whole-life cost. Option X29 can also be used to act in the same way as the (negative only) performance damages that can be built into the contracts of the Institution of Chemical Engineers (IChemE), sometimes favoured for process contracts; the schedule of guarantees included in the Fidic Yellow Book; and the performance guarantees available in the Fidic Silver Book.

Water transfer scheme example

In the pipeline and pumping station example, the bid document would include the performance table in contract data part two and require the bidder to state and guarantee the performance level, in this case the specific power consumption of the system in kWh/m3 of water delivered to the storage reservoir. The bid evaluation mechanism would include: the net present cost of the energy consumed over the life of the asset based on the specific power consumption offered by the bidder; a notional average requirement of the daily volume of water at the storage reservoir; the cost to the client per kWh/m3 of power; the notional design life of the system; and a stated discount factor.

Together, the net present cost of the power would reduce to: net present costpower = A x power consumption offered, where A is a constant. The performance table could state that the amount for not meeting the performance target is, ‘£A for each kWh that the specific power consumption in the power test exceeds the specific power consumption stated in the performance table’. Additionally, to limit the risk on the contractor, for some types of performance it might be appropriate to limit the amount to be paid for missing the target. This is provided for in X29.

The performance table would also need to set out the details of the test required to measure the actual power consumption of the system. The scope could state whether carrying out the test is required as a condition for completion or should be carried out after completion. The test would be either carried out by the contractor and witnessed by the supervisor (typically as a requirement for completion), or carried out by the client and witnessed by the contractor and the supervisor after completion and take over by the client (if the test is carried out after both completion and take over).

The mechanism therefore incentivises the contractor to make sure its design gives the client an asset with a net present cost for power (in this example) no worse than has been offered. The principle could be made to apply separately to performance levels for different things affecting the operational expenditure of the asset that could be guaranteed by the bidder and tested.

Effect of contractor’s design

Other elements of the contractor’s design might affect the operational expenditure but not be easily directly tested and proven. In the example above these might include: the level of automation in the pumping station and so the amount of manning required; the plant and material used for the pipeline (and so design life of plant and material); the replacement cost of mechanical and electrical items during the lifetime of the asset; and annual planned preventative maintenance costs.

Each of the elements could have limits set in the scope and be modelled based on the solution offered by the bidder. If the details of how these are to be modelled can be set out in the instructions to bidders and so the net present cost of these elements can be calculated, the mechanisms could be combined to ensure the bid with the lowest overall forecast net present cost does best in the financial element of the bid evaluation.

Having chosen the bidder on that basis, the instructions to bidders would have to make it clear that the relevant elements of the bidder’s solution must be included in ‘Scope provided by the Contractor for its design’. Then the contractor is required to build the low net present cost solution that it offered as a bidder.

For other elements of the works where the contractor does not have flexibility in its design sufficient to affect the operational expenditure significantly, there is no need to make specific provision over and above making the client’s requirements and constraints clear in the scope.

Combining expenditure incentives

The provisions described in the previous sections can be used to incentivise the bidder to offer a solution with good performance levels, and to incentivise the contractor actually to deliver the good performance levels used to win the contract − and to improve on the performance level if positive incentives are used. As the contractor develops its design, it will always be constrained by the requirements and constraints in the scope – both that provided by the client and (if included) that provided by the contractor.

If the contract is an ECC Option A (priced contract with activity schedule), the contractor and the client know what will be paid for the capital expenditure. As the contractor’s design develops after award, it will make a commercial decision on how much it will spend (effectively at its cost and so taken from any profit in the capital expenditure) to minimise the net present cost of its solution and so avoid performance damages or earn any performance bonus. That decision will be appropriately informed by the value of the performance damages (and possibly performance bonuses). However, there would be no direct commercial incentive for the project manager, on behalf of the client, to collaborate with the contractor to bring down the operational expenditure as the contractor will get all the benefit. This of course is the same for the capital expenditure.

Under ECC Option C (target contract with activity schedule) it is in the client’s interest to work with the contractor through the project manager to minimise construction costs and so increase the cost saving below the target, which is shared between contractor and client as defined in the share profile. The contract does this by comparing the actual defined cost plus fee with the final total of the prices (the target). However, assuming the performance damages correctly reflect the additional net present cost of the asset to the client caused by a failure meet the performance levels, the client will have no direct incentive to help the contractor deliver or improve upon the tendered performance level of the asset. This may not be a significant problem.

If wanted it would be possible, via relatively simple additional conditions of contract, to incentivise directly the reduction of the overall net present cost rather than just the capital cost. This would involve defining the achieved actual net present cost, based on the defined cost plus fee of the capital spend, and the net present cost of that part of the operational expenditure as proven in defined tests as described above. It would then involve calculating the contractor’s share based on a comparison between the actual net present cost and the tendered net present cost. This would then directly commercially incentivise the contractor and the project manager to collaborate to deliver the lower net present cost required by the client.

Conclusion

Incentivisation based on net present cost is logical. The NEC4 ECC with secondary option X29 contains some simple but powerful mechanisms to allow the client to put in place such incentivisation. These could be developed within the structure of the contract to directly incentivise the contractor and project manager to collaborate to achieve a net present cost lower than tendered. Reducing net present cost is likely to reduce the carbon dioxide emissions of the project and so mitigate against climate change.

It may be that X29 will also be used to directly incentivise the contractor to use less fossil carbon – but that is another story.

References

O’Connor, L (2022) NEC publishes new secondary option X29 to help NEC Users progress to net zero, NEC Users’ Group Newsletter, 120.

Patterson R and Trebes B (2013) NEC for designbuild- operate contracts. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers − Management, Procurement and Law 166(5): 260−268.

Patterson R and Trebes B (2015a) Using NEC to incentivise lowest whole-life cost, NEC Users’ Group Newsletter, 75.

Patterson R and Trebes B (2015b) NEC for DBFO – taking best practice procurement into PPPs. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Management, Procurement and Law 168(5): 213–219.